SLAC researchers find superfast collisions predict supercritical fluid properties

LCLS X-rays allowed researchers to connect the molecular dynamics of supercritical carbon dioxide, which is used in industrial and environmental applications, with its unique properties.

By Chris Patrick

It’s a liquid! It’s a gas! No, it’s a supercritical fluid!

Neither gas nor liquid, supercritical fluids exhibit a unique mashup of the properties of both and arise when fluids are pushed to very high temperatures and pressures. Their properties make them ideal for a wide variety of chemical, pharmaceutical and environmental applications.

Supercritical carbon dioxide, for example, is often used to decaffeinate coffee – its liquid-like high density and gas-like rapid diffusion allows it to easily penetrate coffee beans and selectively extract the caffeine while preserving the beloved coffee taste. In carbon capture and sequestration, carbon dioxide emissions are stored underground in their supercritical fluid form to combat climate change. It’s also found in rocket propulsion systems, because it can efficiently store a lot of energy, and the atmospheres of some planets, such as Venus. It could also be used as a more environmentally-friendly fluid in future cooling systems.

Now, researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have uncovered new details of how supercritical fluids’ special properties arise from their molecular level dynamics. Their results are published in two studies in the journals Nature Communications and Physical Review Letters.

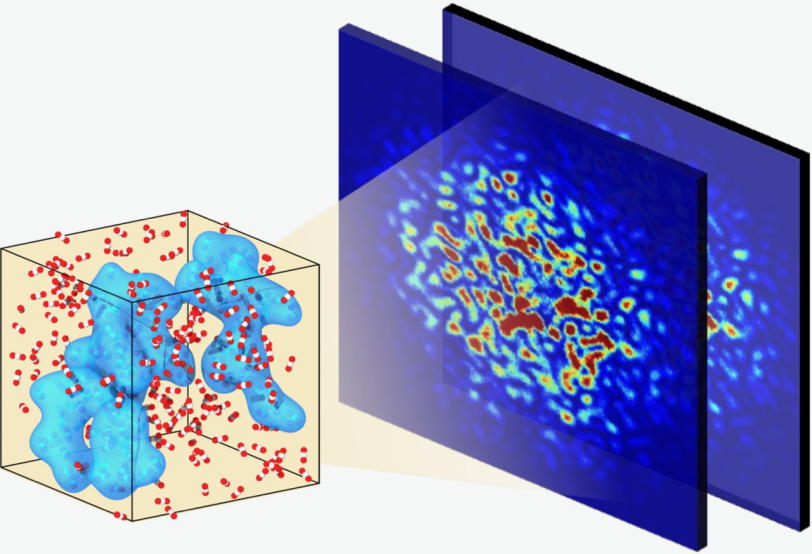

From static studies, researchers know that the molecular structure of supercritical fluids is made up of clusters of molecules of different sizes, but they haven’t been able to study the movement of these nanosized blobs until now.

“Probing these transient, fast-moving, nanoscale clusters is a challenge,” said Matthias Ihme, a professor of photon science at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, a professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford and a member of the Stanford PULSE Institute. The fact that supercritical fluids only form under high pressure and temperature further complicates their study, he said.

However, recent advances in X-ray free electron lasers allowed Ihme and his colleagues to use SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to directly observe the ultrafast dynamics of molecular clusters in supercritical carbon dioxide. Those advances, said SLAC staff scientist Yanwen Sun, involved a decade-long effort to generate two bright, nearly identical LCLS X-ray flashes in rapid succession – making it possible to capture the kinds of dynamics Ihme and his team were interested in.

By measuring how the LCLS’s X-rays scattered off the samples over time, the authors found that the dynamics of these systems evolve within picoseconds, or trillionths of a second. Specifically, these results, published in Nature Communications, showed that the blobs transition from ballistic motion, which is relatively straight and predictable, to the more random and unpredictable Brownian motion.

However, Ihme said, “the existing theory does not capture these nanometer-length, picosecond-timescale dynamics,” so the team carried out follow-up molecular dynamics simulations. The simulations revealed that the observed transition in molecular dynamics is due to collisions between unbound, isolated molecules of the substance with its nanosized clusters.

“You can think of it like a molecular pinball machine, or billiards,” Ihme said. These collisions exchange momentum between the clusters, affecting the properties of the supercritical fluid such as heat capacity, density, and viscosity, which are directly related to how the fluid reacts and mixes, among other behaviors.

“Our measurements indicate that there are significant gaps in accurately predicting properties in these complex environments,” Ihme said.

Equipped with this novel insight, the team developed a theoretical model, published in Physical Review Letters, that connects these microscopic cluster dynamics with the macroscopic properties of supercritical fluids, potentially allowing researchers to predict and tailor them.

“This model is a tool that will allow us to better understand supercritical fluids, to better predict them, and ultimately to control them,” Ihme said. “That’s what an engineer or chemist needs for practical designs.”

In this work, the team focused solely on supercritical fluid carbon dioxide. Next, they hope to investigate the dynamics of supercritical water and the manipulation of chemical reactions in supercritical fluids, which could be used to break down harmful “forever chemicals” into harmless compounds or as environmentally benign solvents for green chemistry and catalytic applications.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citations:

Arijit Majumdar et al., Nature Communications, 3 December 2024 (10.1038/s41467-024-54782-1)

Jingcun Fan et al., Physical Review Letters, 13 December 2024 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.248001)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.